Winner of the 2021 Elgin Award, The Sign of the Dragon is an epic fantasy told in poetry. Of all the things I’ve written, it’s the one that matters most to me. It began with a single poem about a boy chosen by a dragon to be king. I meant the poem to be a standalone piece, but the boy stayed with me, and I returned and wrote more, and more, and more poems about him. Over three hundred poems in the end. (For the curious, the opening poem, Interregnum, appears below.)

Together the poems tell the epic story of King Xau. The story takes place in an imaginary world, but Xau and his kingdom contain Chinese elements, and there are also Celtic and Mongolian strands. The Chinese and Celtic elements crept in because my father was ethnically Chinese and my mother was Irish.

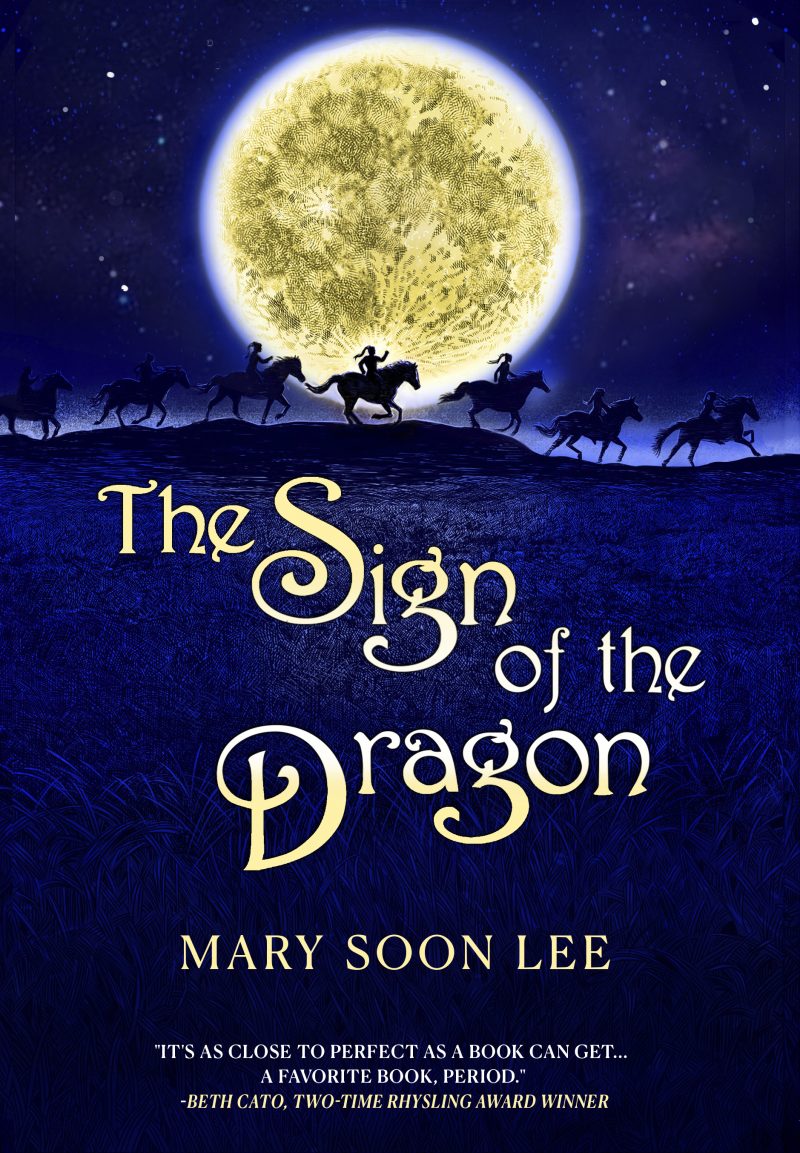

The first print edition of The Sign of the Dragon was published in January 2025 and contains forty extraordinary illustrations by Gary McCluskey. An earlier ebook edition was published in April 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the royalties from the sales of that ebook were donated to the following charities: Doctors Without Borders, Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, and The Trevor Project.

Ordering:

Amazon | Apple Books | Barnes & Noble | Bookshop.org | Kobo

ISBN for 2025 print edition illustrated by Gary McCluskey: 978-1625674913

The first sixty of the three hundred-plus poems originally appeared in Crowned (Dark Renaissance Books, 2015), which won the 2016 Elgin Award, and individual poems appeared in magazines including F&SF, Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, Mithila Review, Spillway, and Strange Horizons.

Note: Signed print copies may be bought from Phantom of the Attic in Pittsburgh (411 S Craig St 2nd floor, Pittsburgh, PA 15213).

Website extra:

For those who wanted one, here is a list of the chief characters and places in The Sign of the Dragon: Principal People and Places

Opening Poem:

Below is the first poem in the book, Interregnum, which won the Rhysling Award, or you can click the play button to hear me reading it.

INTERREGNUM (first published in Star*Line)

Sixteen years old, fourth son,

still they sent him to the mountain

together with his brothers

before their father’s body stiffened,

the kingdom suspended without a king:

four princes, one crown

(a crown he had no use for,

a crown of war, alliances, duty).

He slept on straw near his horse,

displacing the stableboy,

waited for his eldest brother to return

triumphant, ready for the throne–

then brother after brother vanished

into rock and ice and cloud.

The steward took his sword,

his shield, sent him out at dusk:

no torch, no guide, no horse,

no servant, no food, no water.

Snow deepened under his boots;

he waded through drifts,

fell once, twice. The wind mocked him;

he thought of the warm stable,

the bed of straw, his horse,

sleep — but sleep meant death,

so he stumbled on. The wind

called his brothers’ names.

He shouted back his own name;

the wind laughed. Snow fell.

He walked half-blind; sleet kissed

his forehead. The wind said sleep.

He sang to drown it, sang hymns,

nursery songs, drinking songs,

dirges, ballads, marching tunes,

the love songs his mother had favored

(she who was bartered for peace

to a man she’d never met).

He fell, pushed himself upright,

saw a black cloud speed against the wind.

She landed beside him, her breath ash,

snow steaming from her wings.

He knelt, but did not beg,

and asked after his brothers.

“One slept. One fought. One pissed

himself. They didn’t taste like kings.”

She laughed. “And you? What will you

pay for a crown, little princeling?”

“Nothing. I don’t want it.”

She flamed, and he saw himself reflected

in her scales, a kneeling, shivering boy.

“Then why,” she asked, “are you here?”

“Because they sent me.” He stopped. “No.”

He was so tired, he couldn’t think–

“Because the kingdom needs a king.”

He struggled to his feet.

“And what will you pay for the crown,

little princeling? Gold? Men? A song?”

“My freedom!” he shouted at her.

“Well,” she said, “that’s a start.”

*

Years later, on a spring morning,

his queen asked, greatly daring,

about the woman whose name he cried

in his sleep. “Not a woman,” he said,

his heart on the mountain

where he entered his kingship.

The above illustration for “Interregnum” is by M. Wayne Miller.

-

Reviews of “The Sign of the Dragon”

- Tar Vol, December 2025

- Every Book a Doorway, August 2025

- Goran Lowie, December 2021

- Ann Schwader, June 2020

- Beth Cato, June 2020